Seasonal rhythms of our bodies

Seasonal depression, weight gain, more cravings for sweets, or lowered immunity are associated with the change of seasons. According to some hypotheses, deviation from our natural seasonal biorhythms is to blame.

Why are seasonal biorhythms essential?

Humans are subject to biorhythms that greatly influence how our bodies function. For example, in the morning we have higher levels of cortisol, which helps us wake up. But high concentrations of cortisol at bedtime prevent us from falling asleep.

All animals, including humans, have not only diurnal but also seasonal biorhythms. These affect sex hormones, melatonin, the immune system, metabolism, mood, and body weight.

Modern lifestyles allow us to have a year-round summer characterized by the same temperature, light, and diet. This sudden change (from the evolutionary perspective) creates a deviation from our natural development and, according to some theories, can have a negative effect on our metabolism, immunity, mood and, in the long term, our overall health.

Biorhythms are related to health

Many diseases are not equally prevalent throughout the year. Spring rhinitis and allergies occur more in spring, while respiratory diseases occur more in autumn and winter. Much of this has to do with our immune system, which can be weakened due to stress, but also by artificial year-round summer. If we live in the same room temperature all year round, we are less able to tolerate the cold. Perhaps this is why exposing ourselves to the cold through exposure to cold has benefits for our overall health.

But it is also interesting to note that the month of birth is closely related to the risk of various diseases.

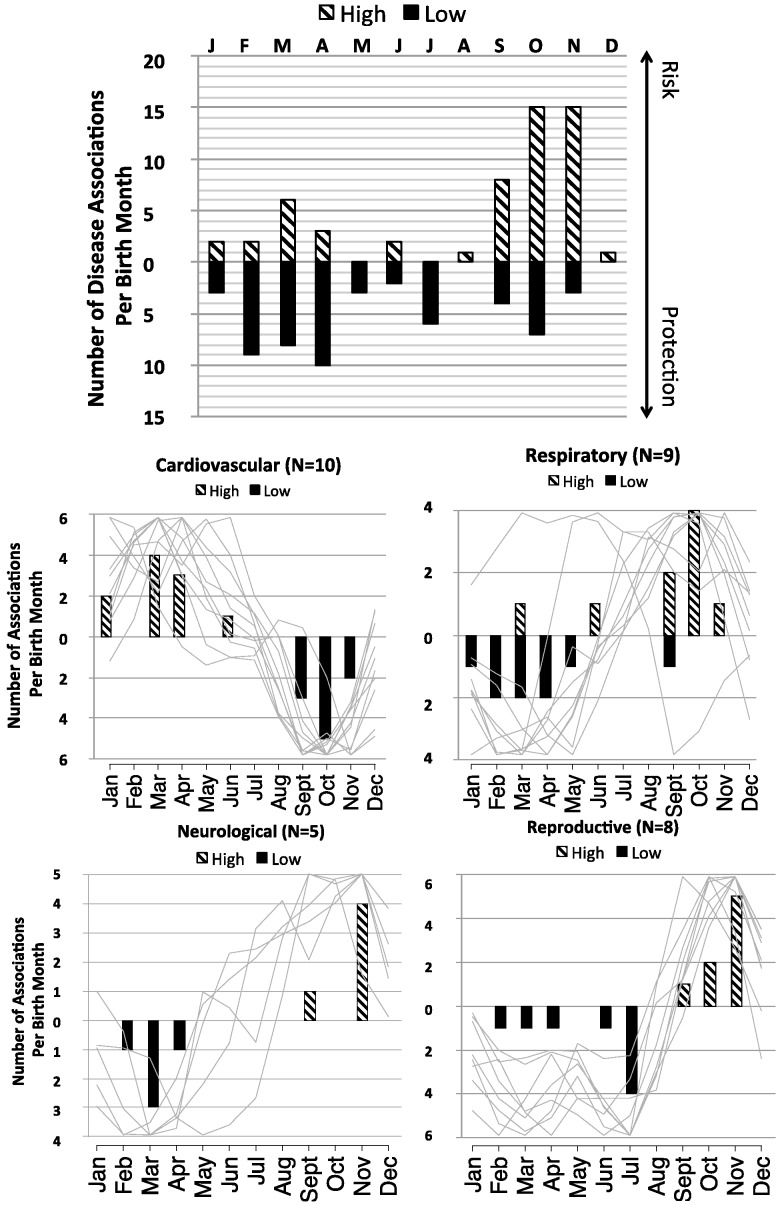

Boland MR’s study looked for a link between diseases and month of birth. They used data from a total of 1,749,400 children born between 1900-2000 in the US of various ethnicities and found a fairly clear association between 55 diseases and month of birth.

Based on their study, we can also see an increased risk for various diseases in children born in the fall. For example, the highest incidence of respiratory disease was seen in those born in October, but at the same time, there was also a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease.

Relationship between month of birth and risk of disease. Boland MR, 2015

Seasonal weight gain effect

From an evolutionary perspective, there are hypotheses that suggest that animals, including humans, have energy storage strategies that allow them to survive periods when food is scarce or unavailable. That is, we are genetically predisposed (thrifty genotype) or guided by earlier experience (thrifty phenotype) to eat a surplus of food in times of abundance in order to have sufficient reserves for times of scarcity. (Andrew D. , 2016)

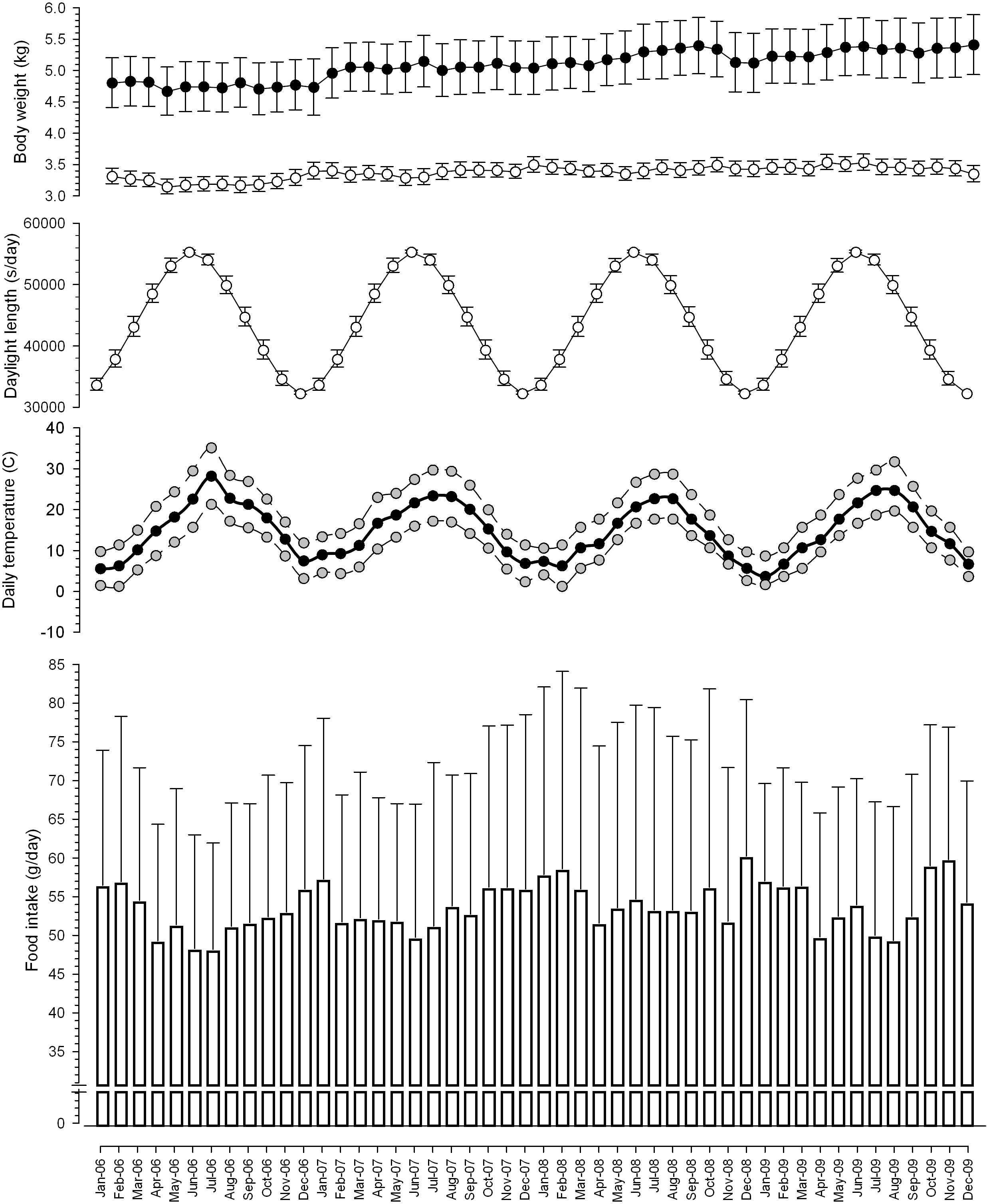

For example, a study on domestic cats shows the relationship of energy intake with season.

Domesticated cats consume more food in winter and less in summer.

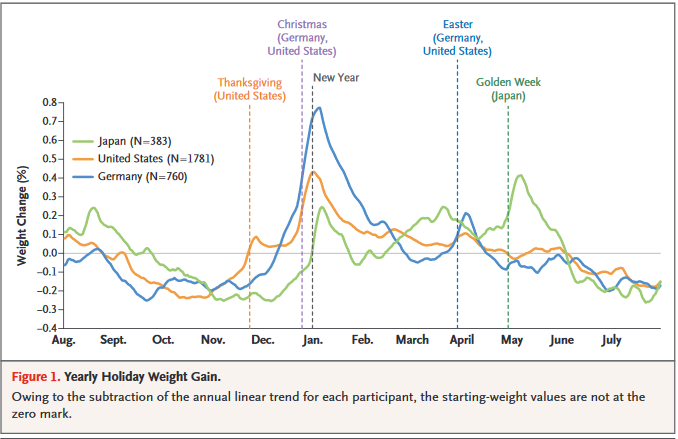

When the average weight gain over the year was measured, it was found that weight gain during the winter holidays contributed the most to the annual weight gain.

Helander EE, et. al, 2016

According to another study (Yanovski JA, 2010), people gain the most weight approximately 0.5kg during the holidays, which they do not lose after.

Is our genetics responsible for the winter weight gain?

To my surprise, they did not find large shifts in physical activity between winter and summer. However, they did find that the women consumed more calories in the winter months (~400 kcal more in winter, ~25% increase) and their resting metabolic rate increased in winter by ~300 kcal, which accounted for ~20% of the difference. The authors explain this by the drop in temperatures.

The end result was that they gained ~1 kg in weight and ~1% body fat in the winter months, while they lost weight and gained muscle mass in the lower body in the spring and summer months, presumably as a result of more activity. (They didn’t take more steps, but they exercised more in spring.)

In terms of diet, the Japanese women increased their protein, carbohydrate, and fat intake in the winter, with a slightly higher proportion of calories coming from fat.

When we look at the aforementioned study of weight gain during the year and the correlation with holidays, we see that the weight gain is connected to the holiday season, not winter. (Golden Week, which is in May in Japan).

In a study on school-age children (Moreno, J.P.), we again see that they gain the most weight during the summer holidays, which are characterized by a change in lifestyle. Children do not go to bed at regular times and their physical activity also changes.

Light, depression, and low energy

Lack of daylight is thought to cause seasonal phase changes in hormone levels, particularly involving melatonin, which in turn may increase the risk of depression.

A systematic review (Øverland S.) on the effect of seasonality on the incidence of depression did not find a clear association between seasons and mood changes at the population level.

Postpartum depression showed seasonal differences, with a higher prevalence in mothers who gave birth in autumn/winter compared with spring and summer.

Tanaka et. al In their study did not find any differences in depression rates between seasons, either.

It is possible that seasonal environmental changes affect everyone to some extent, but not everyone equally. Culture, behaviour patterns, technology, activity and nutrition all have a big influence.

How to manage your energy during the winter season

Some people are affected more by the seasonal changes than others.

While some people can feel mild symptoms that go away within days, people with Seasonal Affective Disorder tend to be withdrawn, have low energy, oversleep and put on weight until the days start getting longer. They might crave carbohydrates, such as cakes, candies and cookies.

Why is that?

Seasonal Affective Disorder is a well-defined clinical diagnosis that’s related to the shortening of daylight hours. It interferes with daily functioning over a significant period of time.” (National Institute of Health)

One of the main regulators of our internal clock (circadian rhythm) is sunlight. When it gets disrupted we experience a feeling comparable to jetlag – tiredness during the day, sleep & wake cycle disruptions, headaches, and even cravings for sweets.

Typically, it is treated by light therapy mimicking sunlight and cognitive behavioral therapy, both of which seem to be effective at combating SAD.

Less light, less energy loop.

According to Kate Solovieva, there are three main factors:

- caffeine,

- alcohol,

- and heavy processed carbohydrates

All three would really come into play in that less light, less energy loop.

“Winter sets off a downward spiral where it’s not just the winter it’s what winter does. Where winter comes and it’s colder outside, and then it gets darker for a much bigger part of the day.

If I now wake up and it’s winter time, and it’s super dark outside, and I’m already feeling less energetic, it’s actually setting me up to now start relying on food, and foodstuffs, and substances to help me moderate my energy. So I’m now feeling a little bit more tired, maybe I’m gonna have some extra coffee throughout the day. Instead of having one coffee, as I would in the morning in the summer, I’m now having two, three, and that starts to kick off that downward spiral because now I’ve had way too much coffee I’ve probably now delayed my breakfast, now I’m feeling super jittery and frazzled by the time lunch time rolls around.

I’m more likely to experience my afternoon crash at 2 or 3 P.M., which is when snacks come in, cookies come in, candy comes in, the vending machine in the office comes in. And then when 5 o’clock comes around I’m so frazzled and hyped up I’m actually more likely to rely on depressants to bring me down, which is often a glass of red wine to unwind, which maybe I am less likely to use in the summer if my energy is high to begin with.

Very often, by November December January we see this downward spirally, energy management feedback cycle, where we kind of go like morning coffee, afternoon sugar, evening alcohol, morning… repeat.”

Is it necessary to change the diet according to the season?

It is sometimes argued that we should not eat the same way all year round, but adapt our diet to the seasons. Thus, we should eat more carbohydrates in summer and limit them in winter.

This statement is based on the evolutionary biology and although some mechanisms exist (changes in hormone levels during the year), they do not circumvent the energy balance.

Sweet cravings and weight gain may be genetically driven, but we don’t have enough human studies to show that the main problem is the annual biorhythm, or eating carbohydrates in winter when they would not be available in our “natural” environment.

A much bigger factor is the behavioural changes associated with the seasons:

- Shorter days result in less spontaneous activity.

- Cooler environmental temperatures are associated with a greater sense of hunger.

- Vitamin D deficiency from sunlight can contribute to less energy.

- Holidays are tightly connected to food, increased energy intake, as well as increased stress. And when we are stressed we tend to reach for sweets and/or alcohol and eat even when we are not hungry.

Kate Solovieva, an expert on nutrition and seasonal affective disorder shared with me in the interview:

I have written recently about an eating experiment I’ve undertaken a few years ago and to this day it remains to be my most extreme nutritional experiment.What I decided to do was to eat only local food for one month. Local Foods were defined for the purposes of that experiment as having come from 100 mile radius from where I was based, so in order for the food to kind of make the list it had to be that local.And that was an incredibly eye-opening experiment for me because sure it’s an experiment taken to the extreme interpretation of what that is, but if I was eating truly local I would not ever be having tea, coffee, black pepper, olive oil, most oils, most nuts, most seafood. Yhat just simply would not be on my list of options.

Sports and seasonal eating:

Athletes train year-round. In practice, this means an increased need for energy and carbohydrates. Therefore, restricting carbohydrates could have a negative effect on overall energy intake as well as the training adaptations you want to achieve through training.

The winter months are a time in some sports when the focus is on building volume and/or building muscle mass. Diet should therefore be tailored to training goals.

As your training goes down, as you don’t have a race on your calendar for maybe six months, well that may be a great time to decrease your carbohydrates, increase protein and fat, and really focus on strength training as you get ready for the next racing season. (Check Base-building nutrition mistakes)

However, if you don’t want to eat fruit in the winter, you don’t have to. You can also get carbohydrates from legumes or cereals 😉

Summary

Seasonal eating is not just about food. Our eating habits and physical activities change with the length of the days.

Seasonal eating has several benefits:

😋Better flavors – Enjoy foods when they are in season. For example, enjoy juicy tomatoes in the summer, broccoli, nuts and mushrooms in the fall.

🥦Higher nutritional value – Commonly produced foods are often harvested before they are ripe and nutrients are lost in transit. For example, broccoli grown during its peak season in the fall had nearly twice the vitamin C compared to broccoli grown in the spring.

💰Lower price – you can save a lot of money by buying local, seasonal food.

Greener for the environment – Fruits and vegetables travel an average of 1,300 to 2,000 miles from farm to store. In the process, a lot of fossil fuels are consumed

🍆More variety – Many people have a problem with variety on their plate. If only it were as simple as following the natural cycle and eating seasonally… Eating seasonally expands the variety on your plate and makes it more engaging. You don’t have to eat bananas all year round.

Here are a few tips to seasonal eating:

❄️Considering seasonal eating, it’s essential to consider location and the availability of fresh produce. In the cooler months you can include root vegetables, dried and fermented foods.

🌄Changing the length of the days affects how we feel and behave. When we are exhausted, we tend to reach for sweets and caffeine. When we are stressed, we may reach for alcohol. These practices deplete our energy. Sometimes it’s better to skip the pizza, caffeine and alcohol on a particularly stressful day and choose more nutritious foods 😉

☀️Don’t forget about Vitamin D. Our bodies have stores of vitamin D, but these are gradually depleting and by October they may be significantly depleted. Therefore, it is advisable to include vitamin D during the winter months. Tip: 100g of sun-dried porcini mushrooms provides approx. 50mcg of vitamin D, a dose equivalent to 20-33 eggs.

❄️Frozen fruits and vegetables are frozen shortly after harvesting when ripe. They retain their nutritional value and are also cheaper than many fresh ones.

Ready to Become a High Performing Athlete?

Sources:

-

Schmitt, S., et al. (2018). Circadian dynamics of mitochondrial morphology and bioenergetics in cultured mouse fibroblasts. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 549.

-

Peek, C. M., et al. (2013). Circadian clock NAD+ cycle drives mitochondrial oxidative metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(28), 11534-11539.

-

Shephard, R.J., Aoyagi, Y. Seasonal variations in physical activity and implications for human health. Eur J Appl Physiol 107, 251–271 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-009-1127-1

-

Tanaka N, Okuda T, Shinohara H, Yamasaki RS, Hirano N, Kang J, Ogawa M, Nishi NN. Relationship between Seasonal Changes in Food Intake and Energy Metabolism, Physical Activity, and Body Composition in Young Japanese Women. Nutrients. 2022 Jan 24;14(3):506. doi: 10.3390/nu14030506. PMID: 35276865; PMCID: PMC8838489.

-

Garriga A, Sempere-Rubio N, Molina-Prados MJ, Faubel R. Impact of Seasonality on Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Dec 21;19(1):2. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19010002. PMID: 35010262; PMCID: PMC8751121.

-

Stevenson TJ, Visser ME, Arnold W, Barrett P, Biello S, Dawson A, Denlinger DL, Dominoni D, Ebling FJ, Elton S, Evans N, Ferguson HM, Foster RG, Hau M, Haydon DT, Hazlerigg DG, Heideman P, Hopcraft JG, Jonsson NN, Kronfeld-Schor N, Kumar V, Lincoln GA, MacLeod R, Martin SA, Martinez-Bakker M, Nelson RJ, Reed T, Robinson JE, Rock D, Schwartz WJ, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tauber E, Thackeray SJ, Umstatter C, Yoshimura T, Helm B. Disrupted seasonal biology impacts health, food security and ecosystems. Proc Biol Sci. 2015 Oct 22;282(1817):20151453. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.1453. PMID: 26468242; PMCID: PMC4633868.

-

Moreno, J.P., Crowley, S.J., Alfano, C.A. et al. Potential circadian and circannual rhythm contributions to the obesity epidemic in elementary school age children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16, 25 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-019-0784-7

-

Øverland S, Woicik W, Sikora L, Whittaker K, Heli H, Skjelkvåle FS, Sivertsen B, Colman I. Seasonality and symptoms of depression: A systematic review of the literature. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019 Apr 22;29:e31. doi: 10.1017/S2045796019000209. PMID: 31006406; PMCID: PMC8061295.

-

Boland MR, Shahn Z, Madigan D, Hripcsak G, Tatonetti NP. Birth month affects lifetime disease risk: a phenome-wide method. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015 Sep;22(5):1042-53. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv046. Epub 2015 Jun 2. PMID: 26041386; PMCID: PMC4986668.

-

Zornitzki T, Tshori S, Shefer G, Mingelgrin S, Levy C, Knobler H. Seasonal Variation of Testosterone Levels in a Large Cohort of Men. Int J Endocrinol. 2022 Jun 22;2022:6093092. doi: 10.1155/2022/6093092. PMID: 35782408; PMCID: PMC9242810.

-

Andrew D. Higginson, John M. McNamara, and Alasdair I. Houston, Fatness and fitness: exposing the logic of evolutionary explanations for obesity , Royal Society, 2016, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2015.2443

-

Serisier S, Feugier A, Delmotte S, Biourge V, German AJ (2014) Seasonal Variation in the Voluntary Food Intake of Domesticated Cats (Felis Catus). PLoS ONE 9(4): e96071. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0096071

-

Yanovski JA, Yanovski SZ, Sovik KN, Nguyen TT, O’Neil PM, Sebring NG. A prospective study of holiday weight gain. N Engl J Med. 2000 Mar 23;342(12):861-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421206. PMID: 10727591; PMCID: PMC4336296.

-

Helander EE, Wansink B, Chieh A. Weight Gain over the Holidays in Three Countries. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 22;375(12):1200-2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1602012. PMID: 27653588.