How is it possible that professional athletes can train harder and more frequently than amateurs? Is it because amateurs train like professionals, but recover like amateurs…training only gives you as much as you can recover from.

Here are some tips for effective recovery.

What is recovery?

After training, the body temporarily has an increased level of free radicals, damaged muscle fibers, depleted glycogen stores in the muscles and liver, and reduced immunity.

Therefore, recovery has several components:

- Repairing muscle fibers

- Replenishing glycogen in the muscles

- Regenerating the central nervous system

- Dealing with oxidative stress in the body

How does reduced recovery manifest?

- Fatigue

- Decreased motivation for training

- Increased sympathetic activity

- Inability to adapt to training load

One bad training session is okay. Three consecutive bad training sessions indicate insufficient recovery.

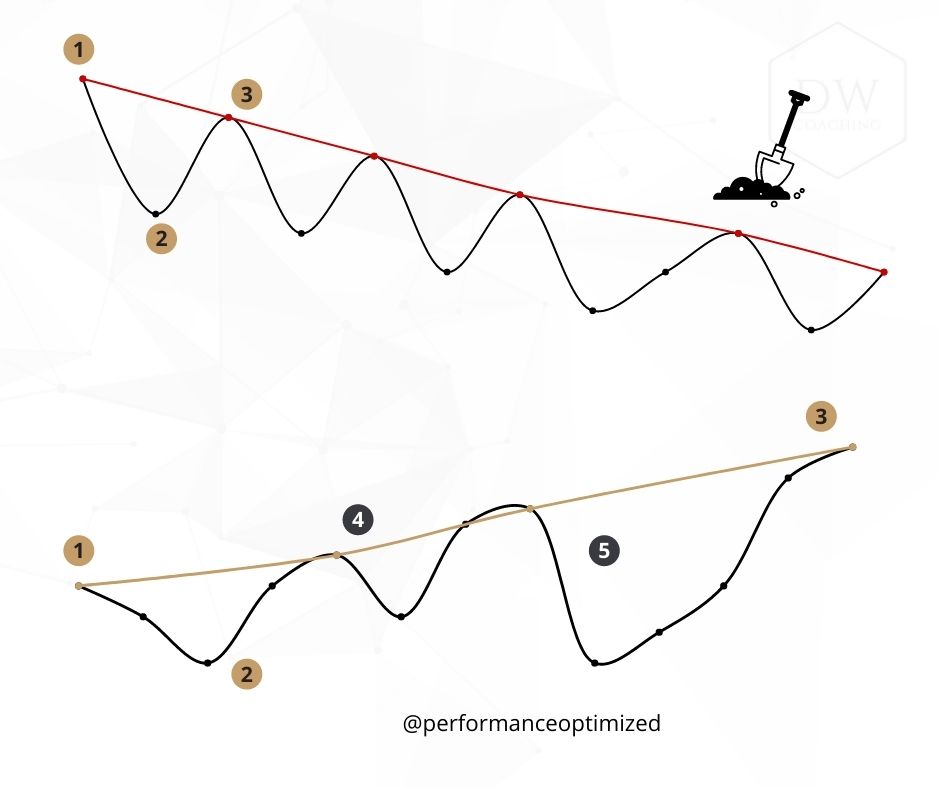

A common mistake, especially among amateur athletes, is when they try to improve at all costs, usually by adding more training sessions, extending their duration, or increasing their intensity. The body may not be able to keep up with recovery, and performance starts to decline. Even with optimal nutrition and sleep, the body needs time because there are physiological limits.

- Initial state

- Exercise-induced fatigue

- Recovery/Regeneration

- Light training – smaller recovery “pit”

- Intense training – deep recovery “pit”

The harder the training, the greater the demands on recovery.

How to optimize recovery?

Nutrition and its impact on recovery

From a nutritional perspective, it is important to consider the quality of the diet, nutrient quantity (energy intake), and timing.

A high-quality diet provides athletes not only with sufficient energy but also supports their long-term health and helps with sleep.

Vitamins and minerals are important for overall athlete health, but in case of inadequate energy intake (caloric deficit), athletes may experience:

- Desired and undesired weight and muscle mass loss

- Decreased performance

- Slowed recovery and subsequent adaptation to training

If such a deficit persists, it can lead to unwanted health consequences (LINK).

Nutrition from a timing perspective:

Within 30 minutes before training

Hydration and fuel

The glycogen stores in the muscles before training play a role in muscle breakdown during exercise. This affects the quality of the training and the time until exhaustion. Less muscle breakdown results in shorter recovery periods. This is particularly important in endurance sports.

During Training

Fuel

Nutrients during training serve to hydrate the body and provide glucose to the brain and muscles, thereby prolonging the time to exhaustion. This is important during long training sessions and in the case of early morning training when the athlete hasn’t eaten anything prior. They also help reduce the feeling of hunger after training.

Within 1 hour of training

Rehydration

Rehydration – the goal is to replenish fluids and electrolytes (especially sodium and potassium).

Replenish 1-1.5 liters of water per kilogram of lost fluids.

You can obtain sodium and chloride from table salt.

Within 1 hour after training

Refueling

Important for high energy demands, multi-phase training, and sporting events (especially in endurance and team sports).

For athletes, it is optimal to replenish 1-1.2 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram and 25-30 grams of protein (if a main meal is not consumed within an hour after training).

Example: Chocolate milk, which contains fluids, carbohydrates, proteins, and electrolytes.

One or more hours after training

Recovery

Post-training nutrition is not just about the so-called post-workout shake. It also includes the meal you consume within a few hours after training.

Omega-3 fatty acids help reduce muscle soreness. Good sources of fats rich in Omega-3 include flaxseeds, chia seeds, salmon, and mackerel.

It is important to have an adequate energy intake and to consume carbohydrates, proteins, and fats from various sources.

Sleep and its impact on recovery

Sleep is important because many processes crucial for health and performance occur during sleep.

Most adults need 7-9 hours of sleep per night. For athletes with a typical intense training regimen, even more hours may be necessary. Many studies show negative effects even with 2-4 hours of sleep deprivation per night.

Lack of sleep in athletes leads to:

- Impaired brain function, which could affect judgment and decision-making during sports performance

- Increased appetite

- Riskier behavior

- Lower ability to repair and build muscles

- Decreased running performance

- Reduced concentration of muscle glycogen (distance covered in time trials)

- Decreased submaximal strength

- Slower sprint times

- Decreased accuracy in tennis serves, poorer soccer skills

It is crucial for athletes to prioritize sufficient and quality sleep for optimal recovery and performance.

TOP 10 recommendations for optimizing sleep for athletes,

based on Vitale, Kenneth, et al. 2018.

- Only go to bed when you are sleepy. If you’re not sleepy, get out of bed and do something else until you feel sleepy.

- Establish regular bedtime routines/rituals to help you relax and prepare your body for sleep (reading, taking a warm bath, etc.).

- Aim to wake up at the same time every morning, including weekends and holidays.

- Strive to get a full night’s sleep every night and, if possible, avoid daytime napping (if you need to nap, limit it to 1 hour and avoid napping after 3:00 PM).

- Use your bed only for sleep and intimacy, not for other activities such as watching TV, using the computer or phone, etc.

- Avoid caffeine if possible (if you need to consume caffeine, avoid it after noon).

- Avoid alcohol if possible (if you need to consume alcohol, avoid it shortly before bedtime).

- Never smoke cigarettes or use nicotine.

- Consider avoiding high-intensity exercise right before bedtime (extremely intense exercise can increase cortisol, which disrupts sleep).

- Ensure that your bedroom is quiet, as dark as possible, and cool (similar to a cave-like environment).

BONUS recommendation from me: Set your alarm clock not to wake up, but to get into bed. It’s tempting to stay up late, but even if you don’t feel sleep-deprived, you may experience difficulties with focus and concentration if your sleep is interrupted. You may also make poorer decisions, which can affect your nutrition and other areas of life.

The impact of stress on recovery:

Whenever you experience mental stress, your body redirects energy away from recovery to cope with the perceived threat.

Your body chooses to allocate energy towards dealing with acute stress rather than improving your fitness. Your energy resources are limited, so your brain has to prioritize what is currently most important.

The second reason why mental stress hinders recovery is that it is closely related to two other driving forces of recovery: sleep and nutrition.

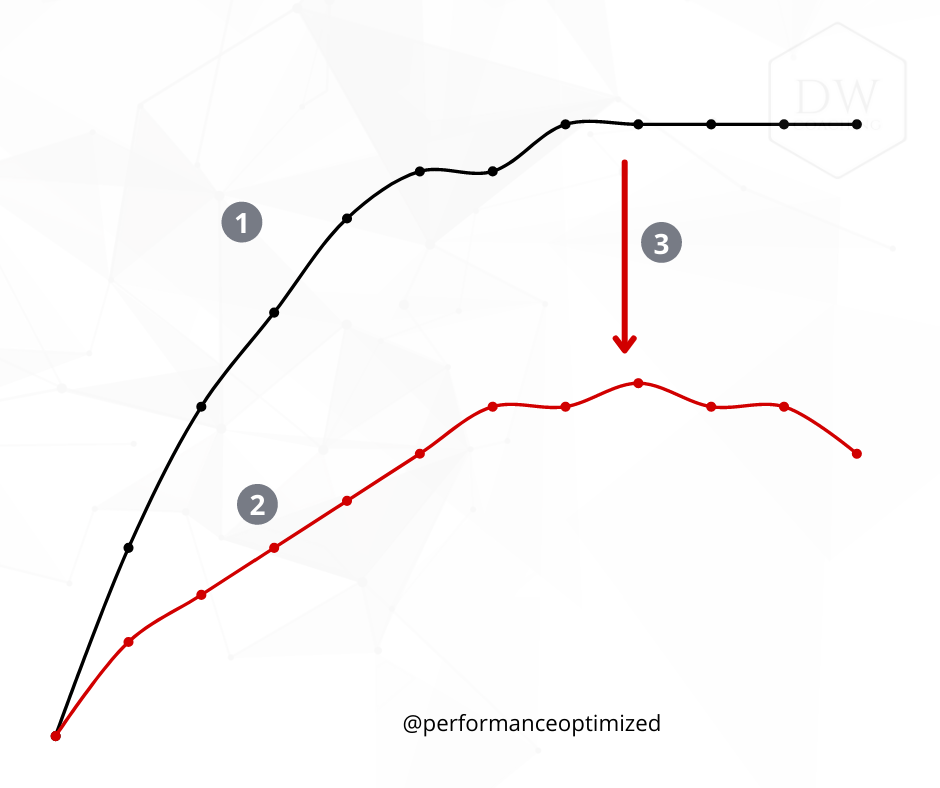

No matter how many calories, carbohydrates, proteins, and antioxidants you consume or how many hours you sleep, your body has physiological limits that are further influenced by stress.

Amateur athletes, compared to professionals, have added stress in their lives, which prevents them from reaching their maximum recovery potential. They burn the candle at both ends.

Stress limits the potential for recovery by affecting three key aspects: 1) Potential recovery, 2) Actual recovery, and 3) Stress itself.

Hidden stressors:

- Environmental pollution

- Air pollution

- Sirens, barking dogs

- Crying children

- Neighbor’s argument in the middle of the night

- Light pollution in cities

What to do?

– Use earplugs or white noise devices to block out noise.

– Use an eye mask to limit light exposure.

– “Toxic” healthy practices

Toxic Healthy practices

Healthy practices such as exercise, training, yoga, clean eating, and meditation are individually beneficial. However, if you try to incorporate too many of them into your life, it can become stressful.

What to do?

– Prioritize the healthy practices that are most important to you based on your goals.

– Reduce the “noise” – a good training and diet plan focuses on the essential aspects and minimizes unnecessary elements.

– Emotional stress

Suppressing emotions

Suppressing emotions and wearing an emotional mask, especially for individuals working with people who need to wear a “mask.”

What to do?

– Create a safe space at home and at work.

– Talk to your friends and family.

– Write down your thoughts.

Information overload

Information is easily accessible in today’s world. Combined with how media shares it, it’s easy to get overwhelmed by conflicting information.

What to do?

– Reduce cognitive load by limiting the time spent watching news and learning things, or limit the number of sources you follow.

– Coaching can help you focus on what’s essential and lighten your mental burden.

Want to improve? Recover like the professionals

To maximize your body’s adaptation to training, consider your personal ability to recover and adjust the training load accordingly. Avoid training longer and harder and hope that your body will adapt.

The goal is to find the threshold where you train at or just beyond your capabilities and support adaptation through nutrition, quality sleep, and other practices. You may find that given your lifestyle, you achieve better results by training less.

How to find your personal threshold?

When working with clients, I first assess their lifestyle, where they experience stress, how they train, and how they are progressing and feeling during training. I tailor my recommendations based on these factors, and we continue to observe, evaluate, and adjust accordingly. The right threshold is not just about what their body allows but also the compromises they are willing to make. This is where science and art converge.

References

Vitale, Kenneth C et al. “Sleep Hygiene for Optimizing Recovery in Athletes: Review and Recommendations.” International journal of sports medicine vol. 40,8 (2019): 535-543. doi:10.1055/a-0905-3103